I recently had the chance to enjoy a lunch with Patrick Esquerre, the founder of La Madeleine Country French Café. Over a delightful meal of mussels and lamb at the impeccable Salum, we discussed Patrick’s career as an entrepreneur and philanthropist.

Patrick offered an interesting analysis of the three types of people involved in any successful venture:

- Steppers: The majority of the workforce, which is capable of doing exceptional work but requires strong management to help them see which steps to take next. Their backs are strong but their necks are bent to look at the ground in front of them, not the road ahead. Many businesses can find companies like global PEO solutions which help aid with the management of these employees, especially if the business has hired these employees from around the world.

- Bridgers: Those who can see the opportunities ahead, but who tend to be head in the clouds. They are more focused on the future … without necessarily how to take the steps to get there.

- Bridger-Steppers: Those rare leaders who can both see the future as well as the steps that it takes to get there.

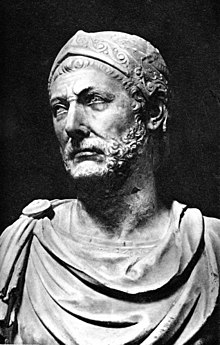

On the latter, he cited examples such as the brilliant military commander, Hannibal the Great, who not only envisioned a way to beat the Romans by leading his war elephants over the Alps, but had the capacity to motivate his armies to do so.

In the world of social enterprise and nonprofit management, we need more “bridger-steppers” who are capable of balancing the relentless pressure of today with the focus on improving the situation tomorrow.

This is no small feat. While our peers in the private sector can rely on executive leadership, we generally must rely on legislative leadership (as discussed eloquently by Jim Collins in his brief but wonderful volume, Good to Great for the Social Sectors). This is quite a challenge, particularly when most nonprofits are saddled with the burden of a constantly rotating volunteer governing board whose members are largely uninvolved in the organization’s daily operations (particularly fundraising). Worse, they are largely unaffected by their own poor performance compared to their peers on for-profit boards (whose incomes will be affected if their company under-performs).

Add to this the pressure of under-resourced staff teams and the chronic impoverishment of the philanthropic “annual recapitalization” financial model, and you can see why most leaders capable of being “bridger-leaders” either go into the corporate sector … or, increasingly, just start their own private venture. Entrepreneurship is a noble pursuit with its own immense challenges, but what our world needs is for more of these talents to be harnessed by the social sector. Only then will we see large-scale progress against poverty, illiteracy, disease and a faltering sense of genuine community among people at all levels of wealth.

Or, as Collins might say, we need the great to focus on the good.

I too have met this brillant gentleman (Mr. Esquerre) and I am delighted you published his wise words for review.

Thanks to Rebekah Basinger for her interesting retort to this blog here.

Here was my response, which I am putting here:

“Nice article — and thank you for continuing the conversation that I started on my blog. I think that we agree more than you expect, though I appreciate your focus on that one paragraph from my blog as a launchpad to start a new article of your own.

My point was not that we should give up on boards, and certainly not abandon the idea of governance. Rather, the primary point of that article to highlight the particular need that nonprofits have for “bridge-steppers,” in the words of the article’s main source, Patrick Esquerre. I brought up the items you quoted as examples of the particular reasons for this.

I am not against boards. Many are high-functioning, and most of their members are there for the right reason (although it is indeed naive to think that 100% are). However, the governance architecture that oversees nonprofits is flawed. While I generally focus my comments on human service nonprofits (as opposed to arts, etc.), I defend my point that most boards are comprised of people who do not understand the reality faced by the organization’s clients; this is simply the nature of such entities, which are more typically comprised of the donors than the recipients of services.

Additionally, my point regarding boards not facing the ramifications of their actions is a very harsh one, but a true one. If a nonprofit board makes a series of bad decisions that result in the shuttering of the organization, their lives are largely unaffected other than socially/emotionally. Whereas for-profit board typically have major financial ramifications if their company folds, their non-profit peers simply stop showing up for their board meetings, stop taking conference calls… and stop being asked for money.

The ramifications of such a failed board’s actions are felt by its clients (who no longer receive services) and by its employees (who no longer have a job). And yet while the former are occasionally represented on boards, they rarely hold more than 10% of board seats. And the latter are generally forbidden from being placed on the board — indeed, the tax filing for nonprofits requires them to report the income that their board members derived from the organization in order to ferret out any possible “conflict of interest.”

I’d like to put forth the argument that such people do not have a conflict of interest, but a vested interest in the organization’s success. Obviously, matters such as compensation and employee benefits would need an impartial governing structure to review and accept changes, but that is such a rare occasion that it seems odd to formulate the entire governing structure of an organization in such as way as to avoid this dilemma.

(Sorry to write a reply longer than my original blog. )

)

Looking forward to continuing the conversation!”